It is extremely difficult to face hard truths, whether historic or present realities.

The temptation is to imitate the myth of the ostrich, and bury one’s head in the sand. Case in point: when I was in law school and married with two young children, finances were extremely tight. We relied on student loans, food stamps, and the little money I earned in the summers.

Still, when it got to the end of the semester, I never quite knew if I’d have enough money to cover rent. Rather than budget, to face the reality of my finances, to stare unblinking at my Wells Fargo checking account, I preferred to look away. I took a more “spiritual” attitude: “God will provide,” I blithely replied to my wife’s probing. We always made our rent payment, but I did not love my wife well in the process. My attitude was fundamentally selfish and lacking in charity.

In a similar way, as a faithful Catholic who loves the Church, and a patriotic Midwestern American, I’d like to think that my Church and my country have not participated (and do not continue to participate) in racism. That they have not perpetuated, for example, the plight of African Americans. I don’t always like to face the truth that members of the faithful have not only refused to stand up against injustice, but have at times actively perpetrated violence and racism towards Blacks and others.

And surely it is disquieting to consider that perhaps I have turned a blind eye or two from evil, racially motivated or otherwise.

In a recent article in the magazine First Things, Gary Saul Morson calls Fyodor Dostoevsky’s novel The Brothers Karamazov the “greatest Christian novel.” In the essay, Morson gives an extended analysis of Ivan, the most rationalistic of the four brothers, who claims that “everything is permitted.”

Dostoevsky tests Ivan’s theory by making him aware of a plot to kill his own father. Ivan’s half-brother Smerdyakov gives Ivan enough information to know that if Ivan leaves town, either the eldest brother Dmitri will kill their father, or Smerdyakov himself will—and frame Dmitri for it.

Morson writes:

“Feeling that Smerdyakov has deeply insulted him, Ivan has an urge to beat him. Had he done so, or even considered why he wanted to, there would have been no murder. Instead, Ivan chooses “not to think.” And this is one way evil happens: We arrange not to know something that would oblige us to act. Our wishes are realized “against our will,” but we have willed that very situation. Whenever our thoughts approach the unwanted information, alarm bells go off and we direct our attention elsewhere. In this way, we provide ourselves with a spurious alibi. As Ivan leaves town the next day, he finds himself saying, “I am a scoundrel!”—but, again, does not ask why.”

Ivan tricks himself into believing that he will have no moral accountability for the death of his father if he simply refuses to think. And anyway, if “all is permitted,” certainly intentional or negligent ignorance is not morally culpable, right? One cannot be blamed for someone else’s actions. Isn’t it the case that I bear no responsibility—and should incur no guilt—if I am not an active participant in another’s evil?

Through the character of Ivan, Dostoevsky shows the falsehood of these claims. Like Raskolnikov in Crime and Punishment, “Ivan becomes more and more overwhelmed with unbearable guilt,” until eventually he goes mad. Why? Because Ivan has deeply experienced in his own soul what the saintly monk Fr Zossima teaches, that “Everyone is responsible for everyone and for everything.”

Wow. Everyone is responsible for everyone and for everything. It is tempting to simply dismiss this line as sentimental blather. Truly, I can’t be responsible for everyone and for everything. I’m not God, after all.

But then I’m reminded of notions central to the Church’s teaching—like the Kingdom of God, and the Communion of Saints, and the Mystical Body of Christ—and wonder: “what is my role in the here and now; as a baptized Christian, what is expected of me?”

No longer simply an individual pursuing my own desires and wishes, I have been purchased and belong to Christ’s Body. I in some very real and tangible sense owe something to my brothers and sisters. Justice demands something of me. Ivan’s guilt and despair reveal what happens to those who ignore their moral responsibility to their family. Are we not all brothers and sisters in Christ now?

But what does this have to do with race in America and the Church?

I’d like to think we don’t have a race problem in America. I’d like to think we don’t have a race problem in the Church. I’d like to think that the police shootings of young Black men in the Twin Cities over the past several years had nothing to do with race. But am I imitating Ivan, directing my attention elsewhere whenever alarm bells go off? While I wish for the best, am I complicit in the worst?

The current and historical facts are hard to bear. My alma mater, the University of St. Thomas in Saint Paul, recently revealed that the namesake of one of its residence halls, Bishop Matthias Loras, had participated in slavery by purchasing an enslaved Black woman in Mobile, Alabama.

That was almost 200 years ago. Does the passing of time diminish the present pain? Are there effects of this action, institutionally or individually, that we must face? Or do we, like I am tempted to do, simply say "The past is the past. We must move on."?

But what does moving on even look like?

This past summer, in the midst of George Floyd’s killing and ensuing unrest in the Twin Cities, I read Herman Melville’s piercing account of a slave ship in his novella Benito Cereno. I commend it to anyone grappling with race in America. The tale invokes the complicity of both Americans and Catholics in the horror of slavery, but does so in a manner that suggests the White reader’s own complicity as well.

American ship captain Amasa Delano comes on board the distressed Spanish slave ship, San Dominick, to provide aid. He quickly learns that something is amiss; things don’t feel right; mystery looms. What we eventually learn is that the African slaves led by the slave Babo, bound for the New World, have revolted and overtaken the ship’s captain, Benito Cereno.

The reason Delano cannot perceive the truth? His perception of reality doesn’t allow it.

As Peter Coviello has written,

What Delano looks at is enslavement: subjection and horror, violence and desperation. . . . But what Delano sees is remarkable. He understands the enslaved as faithful companions, bestial but hearteningly devoted in their loves, not quite a different species of being from himself and Cereno but certainly a part of a different, lesser order of creation.

And because of his views of the enslaved, Delano is blind to his own deep complicity with slavery in his shipping business. This blindness allows him to think, “Who would murder Amasa Delano? His conscience is clean.”

But like Ivan, who refuses to see the intrigue playing out right in front of him and refuses to act to save his father, Captain Delano also refuses to see the truth of the situation and act to save the enslaved. Instead, when it is finally revealed to Delano what has happened—that the slaves have revolted—he acts to rescue Benito Cereno and recapture the slaves (who meet a swift form of penal “justice”).

Notably, Benito Cereno is mired in guilt. Perhaps he was finally confronted by the horror of his actions and forced to face the dignity and humanity of the Black people he traded. But not so Captain Delano, who encourages Cereno to move on and forget the incident:

But the past is passed; why moralize upon it. Forget it. See, yon bright sun has forgotten it all, and the blue sea, and the blue sky; these have turned over new leaves.”

But Cereno cannot forget. He dies three months later.

Benito Cereno reveals the importance of not forgetting, and also of testing one’s perceptions, of being willing to engage and face difficult truths. Like the truth that, as one of the notes in my edition of Benito Cereno states, Charles V—the Holy Roman Emperor from 1519 until his abdication in 1556—“authorized the importation of African slaves into Spanish holdings in the New World, effectively opening up the transatlantic slave trade.” Or the reality that Cereno’s ship was operated by Spanish Catholics, ironically bound for the New World where they would pay homage to a Marian shrine.

It is important not to forget the history of slavery and racism in our country, and the Church’s imperfect record on the issue. But not simply to not forget, in order to express White guilt or for purposes of virtue signaling, and leave it at that. As if simply acknowledging past harm is enough for reconciliation.

Nor to not forget in order to advocate for a wholesale rejection of the past, or rejection of specific countries, civilizations, or institutions. Such wholesale rejection is historically inaccurate and unhelpful, because even though White America and White members of the Church are flawed—often deeply flawed—both have also often welcomed the stranger and advocated for racial reconciliation and justice.

This is especially true of Catholic saints and many of our American heroes, sinners though they surely were.

Instead, the point—at least what I think the Holy Spirit is trying to do in me—is to sharpen the empathetic imagination, to stir the will to action, and to increase the capacity to love the entire Body of Christ.

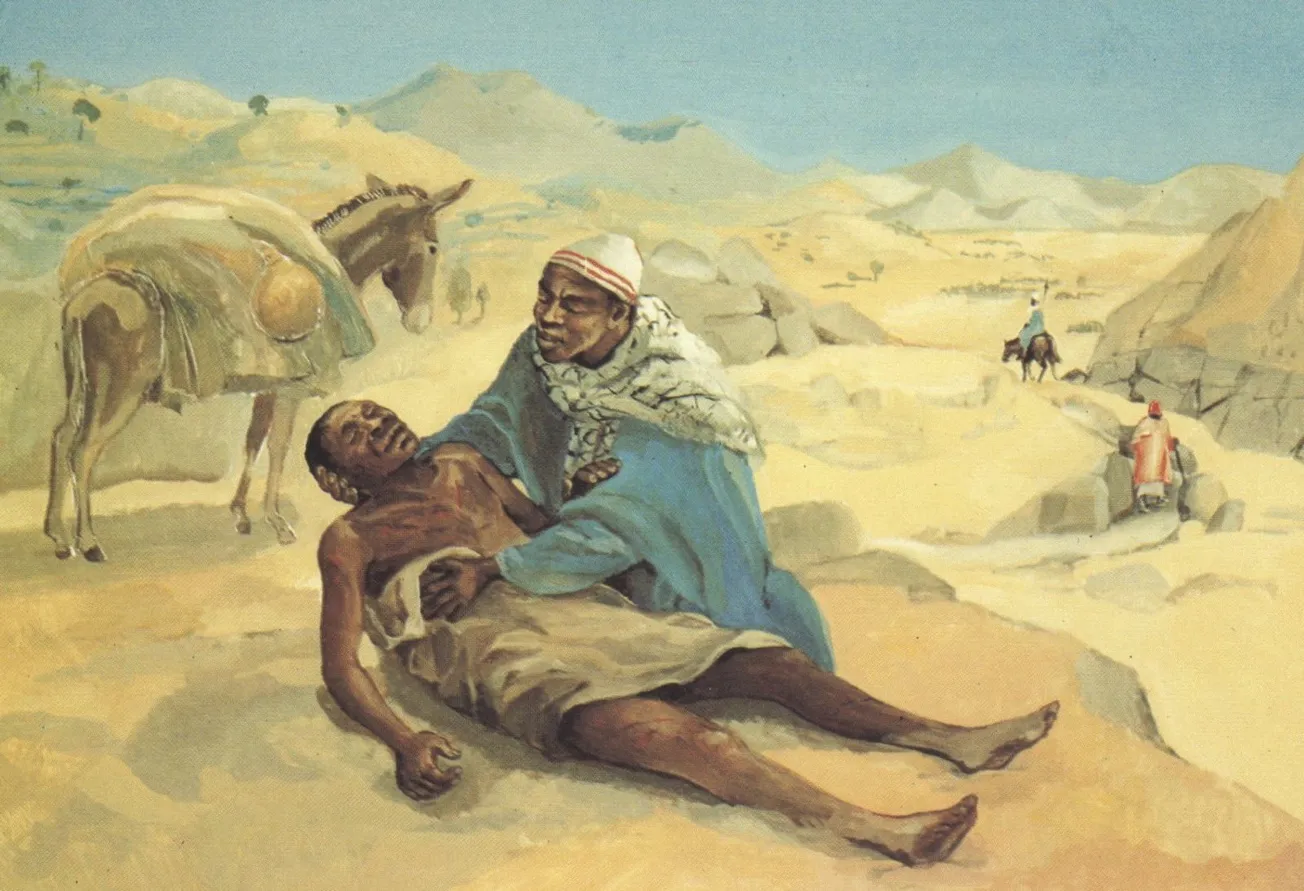

A return to Morson’s essay on The Brothers Karamazov is helpful here. After his father has died and he begins to experience guilt at his death, Ivan has a series of conversations with Smerdyakov to ascertain whether he has moral responsibility for his father’s murder. On his way to the third conversation, Ivan passes a drunken peasant who is bound to freeze to death. Seeing the man, Ivan does nothing. He maintains his passive posture to the world. Then he has the conversation with Smerdyakov, and is finally convinced of his complicity in his father’s murder. Ivan then immediately returns to the peasant and rescues him.

Ivan’s guilt thus has a redemptive quality. Far from numbing his will and making him impotent, he is stirred to action. While he was once selfish and intentionally blind to others, he now performs an act of selfless love.

Actions have consequences. Inaction also has consequences. We are more than we sometimes think we are. We are capable of more than we think we are. And we are capable of love.

Is everyone responsible for everyone and for everything? It seems like too tall a task for any one human. But maybe that’s Dostoevsky’s point: that no person is just “one human” any longer; that we all belong to the Body of Christ; that we all have an equal share in divine love. With that comes awesome dignity. But with that comes awesome responsibility as well.

My hope and prayer for my beloved country and my beloved Church is for true reconciliation and grace and mercy and agape love. And my prayer for myself is to not simply look away. To not simply wish for the best, or hope that things are better or will be better for Black people in America—Catholic, Christian, or non-believer. I pray for nothing short of a new Pentecost.

In our current climate, racial reconciliation perhaps seems impossible. But I take heart knowing, as the angel Gabriel proclaimed, “With God, nothing will be impossible.”

Jeffrey Wald lives with his wife and five boys in the Twin Cities. His work has appeared in periodicals such as Dappled Things, Touchstone, The Front Porch Republic, and Genealogies of Modernity.