On January 5th, 2022, a 125-year-old injustice was set right in New Orleans. It was a quintessentially Black Catholic story.

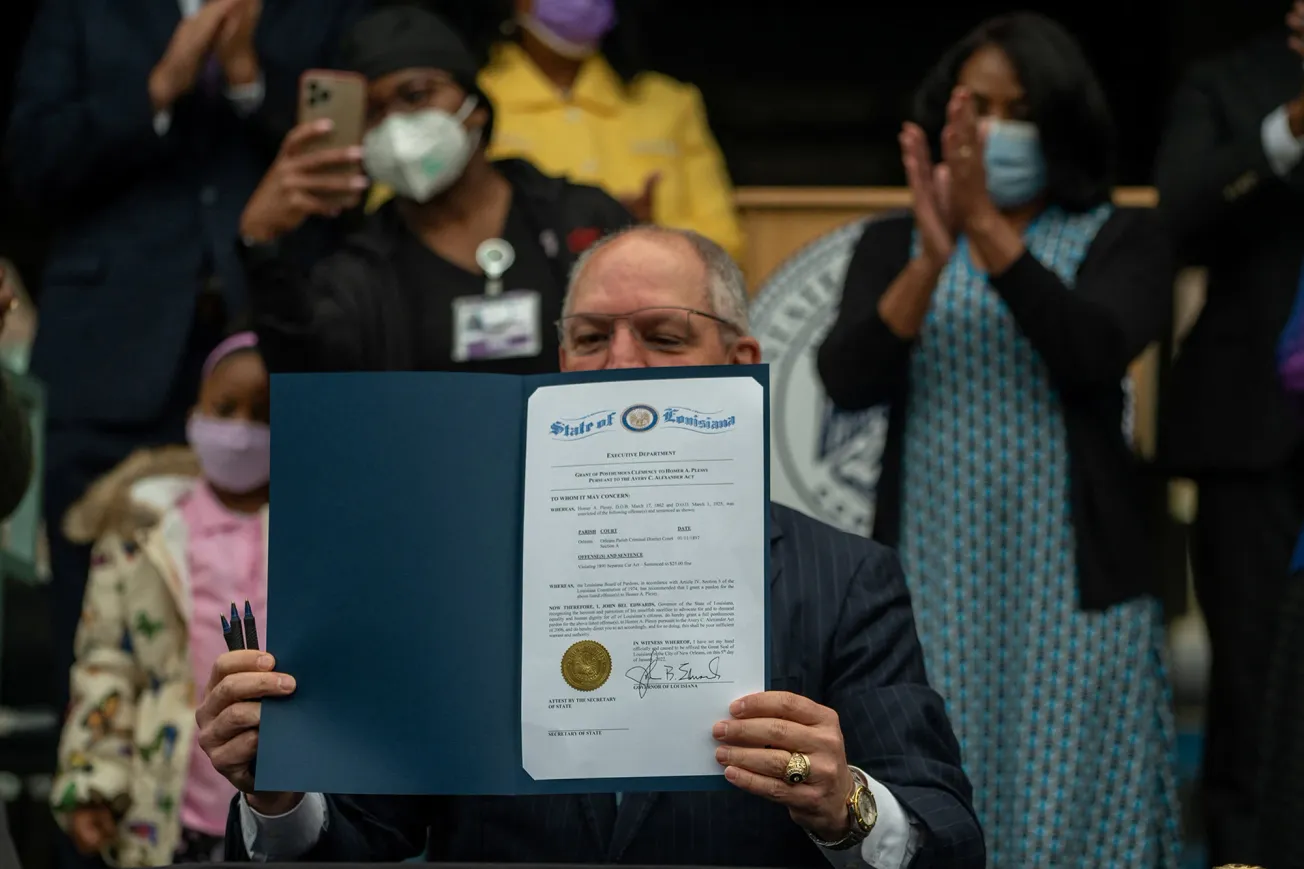

Louisiana Governor John Bel Edwards, himself a Catholic, was joined by descendants from all sides of the infamous Plessy v. Ferguson verdict to officially declare that the late Homer Plessy was not guilty of a crime for riding in a “Whites only” streetcar in 1892.

Mr. Homer Plessy is officially pardoned by the State of Louisiana. There is no expiration date on justice. #lagov pic.twitter.com/U7Xf4tP169

— John Bel Edwards (@LouisianaGov) January 5, 2022

The posthumous act came two months after the state pardon board voted in favor of the proposal in November—oddly enough, during Black Catholic History Month.

Plessy, roughly 30 years old at the time of his bold boarding, was a notable figure in the proto-Civil Rights Movement, having worked with the Comité des Citoyens (“Citizens Committee”) since at least his mid-20s in the fight for racial justice.

It was, in a way, one of the early Catholic social justice groups in America, and involved a number of African Americans.

A “free person of color”, Plessy was himself 1/8th-Black, born in Louisiana just after the start of the Civil War. There, racial dynamics had only recently devolved into the more hostile binary of Black-White division, with the latter holding terroristic power over the former.

Indeed, the territory had only become American in 1803, occasioning the change, prior to which it traded hands between the French and Spanish—both of whom practiced slavery but did not resort to outright apartheid in their dealings with those of African descent.

Once admitted as a state in 1812, Louisiana quickly became a part of the larger nightmare of 19th-century American jurisprudence, in which new US territories were also quickly admitted into race- and slavery-based controversies, often ending in violence.

Louisiana was no exception, with Black freedom quickly eroding until it was restored, briefly, by the end of the Civil War and the early years of Reconstruction. In quick succession after 1864, Blacks gained the US civil rights to vote, attend public school, marry White people, and hold public office.

These were the early years of Plessy’s childhood, when he attended historic St Augustine Church in New Orleans’ Tremé neighborhood and lived the life of a typical Creole of color, learning a trade and preparing to enter the business world.

Soon, however, the party was over. The federal government, deciding that the election of a certain president was more important than human rights, agreed to end its support for Reconstruction in 1877. Barely 15 years removed from their own rebellion against the United States, White Southerners were re-granted full power and used it to once again subjugate Black bodies and rescind their rights.

Raised in a French-speaking family, Plessy would choose to live out the principles of two bygone eras: that of the mainland European colonialism of his ancestors, and the Radical Reconstruction of his youth.

Thus, when called upon by the Comité to illegally board a White streetcar—and indeed declare his Blackness to the operator, as it apparently was not obvious—he rose to the occasion in the hopes of a successful court case. He was promptly arrested as planned.

His dream would be deferred, however, as it became clear that the local judge, John Howard Ferguson, would not submit to his reasoning, that racial segregation was unconstitutional. The case quickly rose through the courts, reaching the US Supreme Court in 1896.

There the court ruled 7-1 that segregation violated nothing, and that the post-war amendments had no power to regulate private enterprise and social prejudice. The only justice to agree with Plessy and the Comité was one John Marshall Harlan.

For the next six decades, “Separate but Equal” was the law of the land nationwide, infecting not just private businesses but public spaces and education as well, lasting until Brown v Board struck it down in 1954.

As with many unsuccessful Supreme Couty trials, Plessy’s returned to the lower courts and was re-litigated in 1987. While he is a legend today, his only reward during his life was in fact a debt: the $25 he owed for violating the Separate Car Act. The Comité paid the due and died a quick death.

Plessy himself died in 1925 in his early 60s, during the height of Jim Crow, and was buried in New Orleans. He has since been honored with a historical plaque at his tomb, and also at the site in his former neighborhood where he first boarded the streetcar. The nearby street was renamed after him in 2018.

The latter two honors were attended by the aforementioned descendants of the Plessy case, including Keith Plessy and Phoebe Ferguson, who formed the Plessy & Ferguson Foundation in 2009 with their respective family members.

They marked the 125th anniversary of the Supreme Court ruling last May, and continue to work for the full recognition of Plessy’s work, that of the Comité, and the ongoing need for racial justice and reconciliation in the present day.

(Do remember, of course, that anti-Black segregation continues largely unabated in America today, and is said to be increasing.)

The anniversary of Plessy's death will arrive on March 1st, which this year happens to also be Mardis Gras, a day of raucous celebration in the Black Catholic community—especially in New Orleans. A fitting holiday for a feast day.

The 130th anniversary of Plessy boarding the streetcar will come on June 7th—roughly two weeks before Juneteenth.

Nate Tinner-Williams is co-founder and editor of Black Catholic Messenger, a seminarian with the Josephites, and a ThM student with the Institute for Black Catholic Studies at Xavier University of Louisiana (XULA).