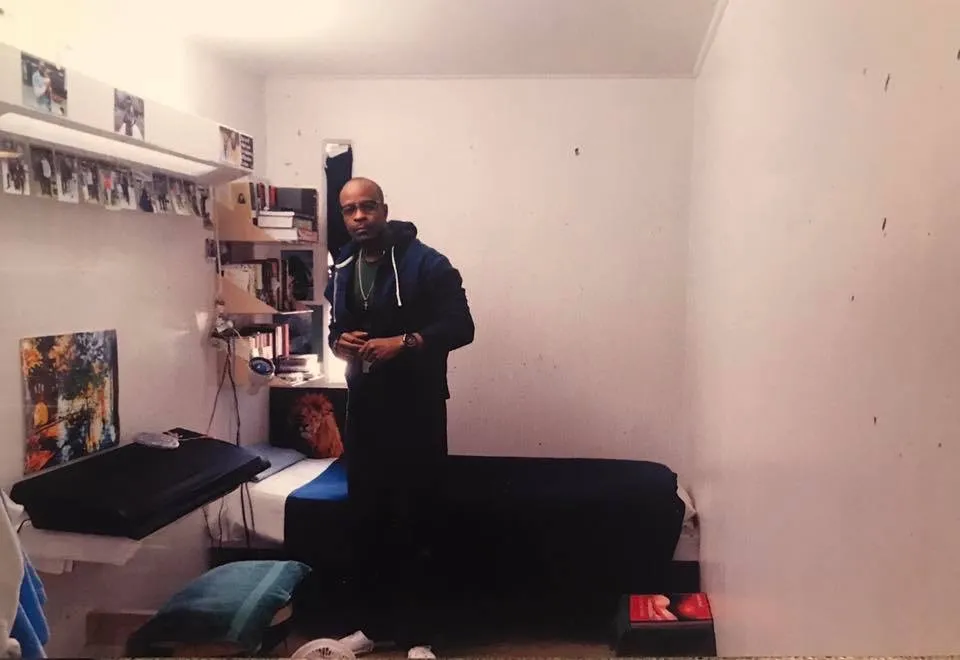

This final portion of our interview with Keith "Bomani Shakur" Lamar is continued from parts 1 and 2 and has been edited for length and clarity.

Alessandra Harris: You wrote a book titled “Condemned” that talks about your case. Can you tell us more about it, as well as what you want people to understand about how social justice and racial justice are all integral to the issue of incarceration and the death penalty?

Keith Lamar: When I underwent this whole process of demanding a trial, being found guilty and sentenced to death, all throughout the whole process, I was advised to remain silent. The obedient person that I was, that's the only thing that I learned from the education system in this country—to be obedient. I learned that, and I kept my mouth closed.

Guys got on the stand and lied on me. Even after an all-White jury sentenced me to death, even after I was thrown into solitary confinement, over and over again I was advised to keep my mouth closed.

18 years went by, and during that time, nieces and nephews were born, and I wasn't able to hold them or hug them. I filed a civil suit back in 2005 or 2007 or so, and we went eight years trying to get the judge to grant us the privilege for me to touch my family. After eight years, the judge said that there's nothing he could do. That's what people don't understand. They think that the system is set up to deliver a resolution, but it's set up to do the opposite of that. It’s set up to wear you out, to use all your energy and resources so that you can’t fight anymore.

After eight years, the attorneys who were working on my behalf said ‘We did everything we could do, Keith. Our hands are tied.’ I just didn't accept that. I was no closer to touching my loved ones. So I went on a hunger strike, and in 12 days achieved what all that hard work by these other people couldn't achieve. I was granted the privilege to touch my family.

That really taught me something about the system: that it’s not really these people’s job to give us justice, equality, to give us respect. That's our job. If you have a proper education, you understand that. That's what education is supposed to inform you, to arm you with. To understand that this is your life. This is your responsibility. Once I learned that, once I fully learned that, I began to utilize my agency.

I wrote a little book, “Condemned”, as a pamphlet, a bare-bones description of what I had undergone. One of my friends told me that I need to expand it and offer it to a wider audience. She was compelled enough to read my story, to believe in my innocence, and she felt that other people would be similarly affected.

She and I worked together for about 11 months, and we wrote the book. It filled in some of the gaps that my little pamphlet had left out in terms of my story: what happened to me in the courts, what the trial court did, so on and so forth.

If anything positive comes in my case, it would be in large part because I wrote that book. It is impossible to go to all these different places that my book has gone. So because of that book, we have a growing campaign around my execution date, and the book has played a large part in that.

AH: For people who are reading this interview, what can they do to help you and advocate for your life?

KH: There are various things that we have put on the website. If people want to donate funds to help me legally, there’s a place they can do that. They can go to my website keithlamar.org and Justice for Keith Lamar on Facebook. They can also order the book.

My campaign and I are involved in various outreach programs like the literacy project. They can donate books to that. Someone who might be listening to this might have a favorite book that changed their life, and they could donate those books to the project. We put those books in the hands of young people who need to read those kinds of things.

There’s also a link on there to my documentary. And if people feel so inclined, they could sign my petition. The more energy that we have moving in a certain direction, the more likely it becomes that I might get a fair hearing one day.

It's really about people gathering around these issues, not just my case. People came together around George Floyd, and the officer who murdered George Floyd is now sitting behind bars. That's what needs to happen. Don't wait around until your son is killed. Don't wait around for your son and father to be put on death row, or until your daughter is murdered. It should be enough that Breonna Taylor was murdered. That should be enough to motivate you to get involved. That’s the only sign that you should need. You don’t have to wait for thunder and lightning; just go by the clouds.

People need to figure out how to cultivate community, how to cultivate solidarity. Those things, not by coincidence, have been removed from our community. When people come together to voice or air their grievances, get on the same page and figure out a way to engage with the powers that be, those things need to happen. We need to implement those things and bring those things into our community. We have to see the need and feel the need that comes from awareness and a sense of being together. God helps those who help themselves. That's an old adage, but I think it has a lot of truth to it.

We’re engaged in battle. I think we have to view it as such. People dying need to be saved. The way we save young people is by engaging with them and giving them what they need. Whether they are related to us personally or not. Whether they have our last name or not. We have to take on that obligation, and that requires expanding our definition of what it means to be Black. What it means to be a human being, ultimately.

That’s what I’ve done. I know it’s not just about me. I also know that the odds of me escaping these people's clutches are slim to none. I’m doing what I'm doing because it needs to be done. Not because I think these people are going to change. I’m doing this because I'm a man. Because I'm a human being. It’s required of me based on what I've learned.

AH: So as the title of our publication implies, we are Black Catholics. Just a couple of weeks ago, a representative for Pope Francis wrote a letter to Missouri Governor Mike Parson to grant clemency to Ernest Johnson, and stated, “The Pope wishes to place before you the simple fact of Mr. Johnson's humanity and the sacredness of all human life.”

What would you want people on the outside to know about the humanity of people on the inside. Your humanity, that of the other people who are there on death row, and of other people at the supermax prison?

KL: That's a good question. Regardless of why someone finds themselves on death row, we have to respond to the humanity of that person in order to uphold our own humanity. You can’t degrade somebody without degrading yourself. The fact that the country is engaged in this practice degrades the whole country. Not just an individual.

But more than that, this is a Christian country, and you are to assume that we are following the example of Christ. Christ himself was executed – he was crucified. He wasn't the one doing the crucifying. If we are Christians and we are following the example of Christ, somewhere along the way we have gotten our signals crossed.

One of the things that I've learned over the years is that more important than what I profess is how I live my life. Not what I believe, but how I believe. To sit on your couch and wax poetic about people. ‘There but for the grace of God go I.’ That's a real thing. Especially if you’re Black. Especially if you’re poor. Things can happen to you.

George Floyd didn’t commit a crime. He was just walking down the street. Breonna Taylor was asleep in her bed. They dead now. At the hands of the justice system. They were executed. The fact that they received a semblance of a trial doesn't make any difference.

When they follow through with my execution, that will be murder. No different than what happened to George Floyd. What's going on? What are you being asked to condone? Understand that you as an individual have an obligation to stand on the right side of justice. To stand with thinking people, not with the executioners. That's the thing that I think is most important for people to understand. I understand that the Pope has come out against capital punishment, and I think that's a good thing.

I have done so many things that, in hindsight, I wish I wouldn't have done. A lot of people, young people right now, who are on the path that brings them to where I am, they don't understand the full ramifications of what they're doing, because they're still kids. That's what happened to a lot of young people who we are standing in judgment of right now. It happened when they were 18, and when they're killed, when they’re executed, they might be 35, 40 years old, because that's how the system works. By then, you're a totally different person. By now, your prefrontal cortex has developed, and you’re a fully grown human being now who sees things differently. So you’re actually killing a totally different person. People don't have that sense, but they should.

AH: How do you think people of faith can reach the young people that you mentioned? The young people whose brains aren’t even fully developed yet who are in economically depressed environments and may not have the best family structure? How can people of faith intervene in their lives, so we can prevent the next person from being charged and sentenced to death?

KL: When I was growing up, I grew up in a neighborhood founded by people who were a part of the Great Migration. People who came here in the 1930s and 40s to get jobs in the mills and factories, and whatnot.

The lady down the street had permission to admonish me. To chastise me. As far as the community was concerned, I was everybody's child in that village. That’s something that is now gone from us. ‘That’s somebody else’s kid.’ But as we see, oftentimes, despite our refusal to accept our connections, those bullets come and find their way into our homes as well. The drugs find their way into our homes as well, no matter what we have tried to do to stay out of it.

So, if you try to stay out of it, you have taken yourself out of the remedy. You’ve taken yourself out of the solution. You have to stay involved with this young person who today might throw a rock and scratch your car, because that might be a gun 10 years from now that he holds to your head. The here and now is a moment for you to intervene in this young person's life and possibly have a positive effect.

But the only way for you to see it like that is to expand your understanding of who that young person is. That's your child. At least theoretically speaking, we are supposed to be a part of God's family, right? That's something that people need to start taking literally if they claim to be a person of faith. Faith without works is dead. So, if you are not working to remedy the social ills in your community or trying to in some way illuminate the darkness, then your faith is dead. That's a problem. You need a renewal of your faith.

A lot of people who call themselves religious or call themselves people of faith, they use religion as a kind of insurance policy. They live in a way that no matter what they do or don't do, they have this insurance, this ticket into heaven. I like to tell people not so much that I'm a Christian, or that I follow Christianity, but that I follow Christ. I think the distinction is that Christ wasn't, you know, sitting in a church on the throne. He was in the street among the poor. He was feeding the poor, he was saving the poor. He wasn't removed from that. He was right there.

That's what I'm trying to do in my life. I'm trying to be right there. Trying to stay engaged. I'm not focused on telling people about religion or whatever. I'm focusing on telling people what these young people need in order to not become a statistic. This is what Christ was doing. This is what Martin Luther King was doing. What Malcolm X was doing. I’m following in that tradition as best I can.

I'm no Martin Luther King, of course. But I’m trying to live by their example.

AH: Looking back, if someone could have intervened in your life when you were, let’s say, 15 and living on your own, what would have made a difference and put you on a different path?

KL: As I mentioned, I was sent away when I was 13 years old. I came home to the same economic situation, dysfunctional household, and all of that. And I'm away from my grandmother's house one day. There was a church on the corner of the street. They were playing music inside of his church, and I went in and sat on one of the back pews. The preacher asked if anybody wanted to get baptized.

I was 13, but I understood that my life was in danger. People we discard, they know they live in danger, but they don't have the tools and the resource to get out of it. I raised my hand when the preacher asked if anybody wanted to be baptized, and two weeks later, I gave my life to God.

No one in that church stopped to ask me about my living condition at home. I did all this on my own. When I came back two weeks later, I didn't have anybody with me. 13 years old. I was 13 and came to these people. My people. But they didn't recognize me as their own.

Six months before my murder case that sent me to prison, when I was 18 years old, I got baptized again. I knew my life was in danger. But I was caught in this thing I couldn't get out of. My identity was caught up in what I had, not in who I was. I had a Mercedes-Benz. I had gold chains, Rolex watches, and that—as far as I knew—was all I was. But spiritually speaking, my life was in trouble. And I went to the church again and got baptized again. Six months later, I was in this horrible situation where I nearly lost my life.

What I would say to people is that these young people need you. When we first came to this country as Black people, we needed each other. We knew that if we were going to survive, that we needed to rely on each other. We saw some horrible things in those slave ships and on those plantations. But the fact that you and I are having this conversation means that those people found a way to figure it out and stick together.

What we're going through can’t even compare to what they went through. We can read books about the Middle Passage, about Thomas Jefferson’s plantation, what people did to break slaves. People under those conditions understood our only way out was together. Harriet Tubman escaped slavery, and she came back not once, not twice, but over and over and over again. And that’s how many times you have to come back for these young people. That's the only way.

It’s the same way now because nothing has changed. We still need to fight against the same people for the same reason. The same strategy must be employed. We’ve got to stick together. We got to give a damn about each other. That's the only way. Not the American way, every man for himself, but the human way. We got to care about each other and invest in each other’s lives. If we don't do that, things will continue down the path they’re on right now.

AH: Are there any parting words you would like to add?

KL: First of all, thank you for providing the platform. It might be two years from me leaving this planet. I only mention that to give you a sense of my vantage point. Martin Luther King, before he was murdered, had precognition with his speech, and was talking about his vantage point. That he hadn’t arrived at the Promised Land, and that we need to commit ourselves to getting there.

Martin Luther King, Medgar Evers, Malcolm X, people who stood up understanding that they will be killed. Martin Luther King’s house was bombed five times before he was murdered. He knew that he was going to be murdered, because he knew the people who were threatening to murder him, just as I know now.

We have to recognize that we have a stake in what happens to Black people in this country. Think about the young person who you know is walking down your street, whose parents might be on drugs or whatever the case may be. That person might be the next Martin Luther King.

Make the decision to live from your heart. That's what Jesus was about.

Alessandra Harris is author of two novels and is a wife, mother of four, and co-founder of BCM. She has earned degrees in Comparative Religious studies and Middle East Studies and currently studies in the Diocese of San Jose's Institute for Leadership in Ministry. She has also contributed to publications such as America Magazine, Grotto Network, and US Catholic. Her third novel is due in 2022.

Want to support our work? You have options.

a.) give on Donorbox!

b.) create a fundraiser on Facebook