At the age of seven, I experienced one of the most heartbreaking episodes of my life: experiencing separation from my mother due to her incarceration. One particular day in first grade left an indelible impression on me.

I sat alone on the playground bench. The day was illuminating with bright rays, and the joyful laughter of my peers echoed across the lot, yet there I sat in a despondent state of grief. I watched my classmates move in an inaudible, black-and-white manner. A voice like sweet honey broke through my preschool callousness.

“Efran, what's the matter?”

Finally, someone recognized my hurt.

“My momma is in jail and I miss her,” I managed to utter while choking on my words.

With no hesitation I started to cry, and she embraced me with the warmth of a hug that erased my hurt.

Looking back 25 years later, I can say that was an influential moment. No, that wasn’t my origin story on being against the prison industry. On the contrary, I have intellectually wrestled and teetered on this topic. However, when I reflect on the nature of prisons or prison-related entities and the catastrophic harm inflicted on Black families, I sympathize with the countless Black children who are forced to make sense of the new dynamic.

If we can effectively dismantle the racist and exploitative prison industry and create thriving systems that promote healing, accountability, and recovery, we will be targeting the root causes of criminal behavior.

First, it's imperative that we challenge the knee-jerk reactions to “Let's abolish prison.” Upon hearing it, the idea sounds outlandish. For so many who benefit from unbalanced distribution of power, to attack the criminal justice system is to attack the fabric of the country's ideals of justice, fairness, and impartiality. Sadly, when we critically examine these three aspects and rate the prison system and similar institutions—courts, police, etc.—the record doesn't add up.

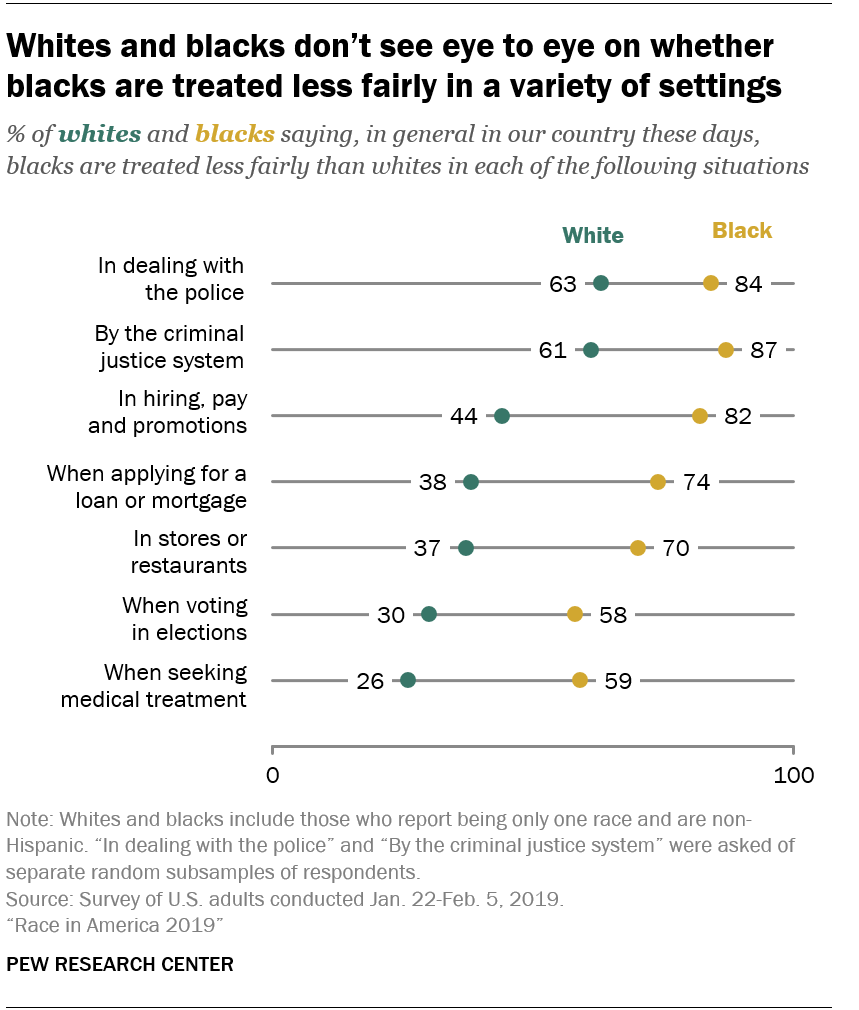

For starters, recent Pew Research polling showed that nearly all Black respondents and even a majority of White participants think Black people get less favorable treatment than Whites in the US criminal justice system. To have nearly the entirety of a historically neglected ethnic/racial group report their obvious encounters with White supremacy is one thing, but even the group with the most power affirms something is objectively wrong with the current system.

Moreover, to counter the popular narrative of the ideals, we have to recognize the level of conditioning we receive from early childhood concerning the complex industry of prisons. The same amount of effort given to “copaganda” and “cops good, criminals bad” must be used to help the masses. At the heart of the argument for eliminating prisons is this: incarcerating people causes a ripple effect of damage. Whether it be detention centers for immigrants or state and federal institutions, the levels of trauma being experienced are significant.

Research suggests that parental incarceration in childhood creates considerable mental and physical health challenges, such as poor access to healthcare, engaging in risky health behaviors, and exposure to adverse traumatic events. In families, incarceration alters dynamics dramatically, causing economic hardships. Data from a national study reveals that women with an incarcerated co-parent are not only forced to find additional jobs, but their limited income can force families to move to areas with a concentration of crime, violence, and inferior schools. Overall, there exists a breadth of scholarship concerning the consequences of incarceration on the family, and of ignoring the catastrophic violence and trauma from carceral institutions.

In light of Catholic teaching, we have to ask: If the family is the “cell of society” and is the fundamental place where socialization and values are implemented, how do we create thriving family units when prisons exist—causing a detrimental chasm in the dignity of the familial institution? In fact, to be pro-prisons is to be anti-family and, ultimately, anti-life.

To authentically be pro-family, we have to abandon punitive justice as the remedy for a crime. To think we can excessively punish someone to reform them is a flawed notion of justice that is obsolete. Simply thinking prolonged periods of confinement to a cell or facility will cultivate a better conscience or moral interior is not the correct path. We tried those methods. We created piecemeal reforms. We held people “accountable” while managing to let them off the hook. The era of attempts at reform is over.

By putting forward a humane alternative to prison, plenty of abolitionists aim for transformational justice (TJ) rather than punitive methods that maintain unfair systems. At its core, the TJ framework wants to understand the ways harm and violence originate, in order to change the systems that create the issue. Moreover, looking at the big picture, TJ affirms true justice because it wants to confront existing concerns of violence but also contextualize the systems that enable it to begin. From a social work perspective, the focus on the person in the environment helps those involved in the TJ process understand how micro, mezzo, and macro factors are associated with harmful incidents.

With its focus on community-oriented solutions, TJ doesn't place hope in systems that perpetuate oppression or inequality. The belief in not relying on the State isn't a radical idea. Because many oppressed groups have distrustful relationships and unbalanced power dynamics with the courts, prison, and other large-scale government agencies, many communities have been developing resources and support at the community level to reduce harmful patterns.

Since our dynamic faith has a powerful spiritual and social justice framework on matters of interacting with the political realm, the Catholic Church can play a role in an abolitionist paradigm. With the papal foundation laid and elaborated on, there exists vital support for the cause.

We can start with Pope St. John Paul II, who set the precedent for dismantling the usefulness of the death penalty in Evangelium Vitae. In addition, he delivered a homily in 1999 that gave a strong denunciation of and call for an end to the death penalty.

Carrying this papal torch, Pope Benedict XVI issued a powerful exhortation shortly before the end of his pontificate, demanding a more humane penal system that elevates human dignity and eliminates the death penalty. The consensus between both leaders is the recognition of the immeasurable exploitation and abuse of the prison system. Therefore a push for just reforms was a much-needed step for ensuring reconciliation and restorative justice. I don't disagree with them, but the fact remains that reform only tinkers with the system. I sense both men would support more local-level approaches that embody the gospel of redemption.

The current Vicar of Christ, Pope Francis, has spoken extensively regarding the death penalty and criminals. Though Pope Francis isn’t an abolitionist, his restorative justice views on prison have a wide influence and bolster the work of ending mass incarceration.

Regarded as a groundbreaking move in his papacy, Francis spearheaded a 2018 revision to the Catechism of the Catholic Church to include prohibition of the death penalty. In his speech to Congress in 2015, he had not only stressed a global commitment to ending the death penalty but expressed that a just punishment must never exclude hope or rehabilitation.

The moment that made me radically rethink the role of punitive justice, however, was when Pope Francis addressed employees of the Italian Prison Police in 2019 and exhorted them:

“If hope is locked up, there is no future for society. Never deprive anyone of the right to start over!”

/cloudfront-us-east-2.images.arcpublishing.com/reuters/BLCI3VMFZFIUZHQXMHRC6CVWRA.jpg)

Pope Francis has consistently reiterated how the role of the death penalty is incompatible with the Christian faith. By doing this, he has opened the role of the Church to be on the vanguard of ushering in a new approach to rehabilitation.

We have a strong foundation of papal authority on this topic within the last 30 years from three humanitarian and justice-oriented popes. This underscores the fact that our modern system based on punitive justice is inefficient and inadequate to offer redemption or reform to someone convicted of a crime. With the boom of global capitalism since the1980s, the inception of the War on Drugs, its relentless attack on Black and Latinx Americans, and the slew of “tough on crime” measures, incarceration numbers have swollen to unprecedented levels.

If the goal were to truly rehabilitate, we would expect a proportionate decrease in crime during this time. Unfortunately, increased incarceration is shown to have a limited impact on crime. We've been “reforming” the system in various ways, with sentencing adjustments, improving prison conditions, and halting the death penalty in several states and at the federal level. Even so, despite the slight bits of change, the gruesome prison industrial complex reigns.

Therefore, it seems clear that the only viable solution is eliminating the carceral system altogether and investing in curing root causes.

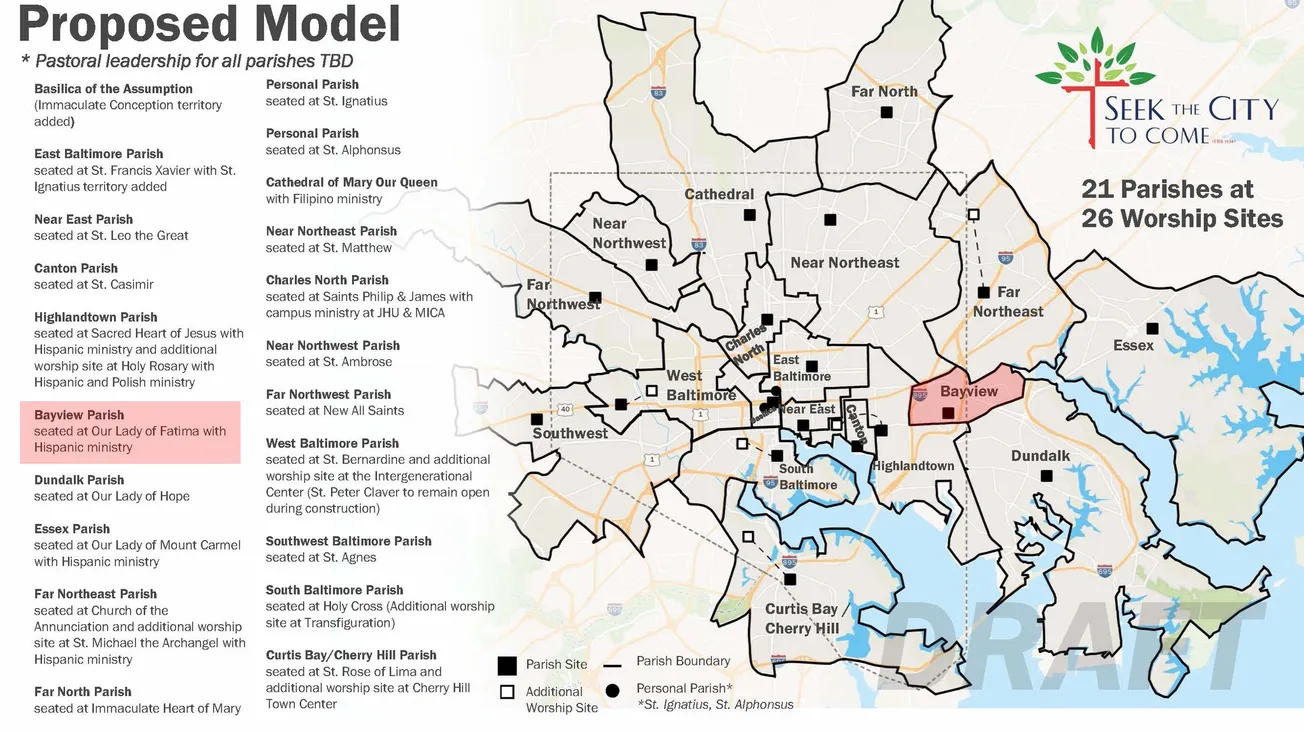

Starting with post-conviction strategies, our Catholic tradition is in favor of subsidiarity, which would entail developing local systems and organizations that have the most access and knowledge regarding the populations at risk. Better-suited, evidence-based interventions or services could be implemented to meet the various needs of the convicted, those with secondhand exposure to harm, and the local community.

This could mean a radical re-investment in social work, child development, sociology, psychology, criminal justice, educators, and a range of related fields delivering high-impact services to address incidents of violence across the country. More importantly, this could be an opportunity to pay a living wage for practitioners in the community who serve as peacemakers.

Finally, to say that God is silent on this matter of the prison system is to misunderstand the biblical portrayal of God. Here is a Being that’s constantly siding with the oppressed, marginalized, or forgotten. Scripture is replete with exhortations to defend the powerless against unjust systems. With so many Black people dying by capital punishment, and in a system rooted in postbellum Jim Crow laws, the blood of our brothers cries from the ground.

For far too long, the sin of Cain has overpowered the dignity and sacredness of Black lives, but God has the final say. In the power of the resurrection, liberation is possible. Through the glorious rising of our Savior, we have full assurance that God hears our petitions and wants us to be emancipated. Ultimately, it's through an abolitionist paradigm that we can start to rebuild our fractured America.

As our savior boldly declared with all eyes upon him in the synagogue: “The spirit is upon me.”

Indeed, we have that same Spirit living and dwelling within us. May He come to our aid to empower us toward freedom.

Efran Menny is a husband, father, and small-time writer. He’s a passionate educator, student of social work, and host of the "Saintly Witnesses" podcast.