The Book of Acts is the chief historical book of the New Testament. Just as those of the Old Testament detail the history of Israel post-Pentateuch, Acts describes the work of the apostles after the Gospels.

In last Sunday’s Mass readings, for the feast of the Baptism of the Lord, we read a portion of Peter’s vision from Acts, which was a major catalyst for the Church embracing the Gentiles alongside the original Jewish followers of Jesus.

Before his Ascension, He had commanded his disciples not to remain in their tiny section of the continent, but to carry the Gospel to the whole world. The Twelve would stay put briefly to preach to the Jews, but in order to carry out the larger mission of the Church, they eventually had to split up and spread out far and wide.

Indeed, if the apostles and the early followers of Jesus had fully understood from the outset the message of the Messiah, they would have understood that this Gospel was not strictly for the Jews but for the Gentiles, too. (Mt 8:11; Lk 2:32)

The engrafting of the Gentiles was finally consummated in Acts 10, when Peter, the head of the Twelve, and Cornelius, a pious centurion, both received visions that would catapult the Church into a new era.

From an angel, Cornelius received instructions to find Peter. Likewise, Peter saw various wild creatures such as beasts and insects. A voice came to him three times saying, “Get up, Peter; kill and eat,” but Peter refused because eating those things was prohibited by Jewish law. In response, the voice declared that all foods are permissible.

This vision revealed that a people once foreign to God and unclean to the Jews would now have the opportunity to be declared co-heirs to the Kingdom. When Peter and Cornelius finally meet, Peter understands this deeper message of the revelations he received: that Christ makes all the members of his Church—regardless of ethnicity, culture, or language—partakers in his divine nature. As a result, Peter is the first to spread the Gospel to the Gentiles.

As Catholics, we believe Peter’s role is no coincidence. In the Gospels, Peter is noticeable as the distinguished apostle Jesus picked to be the shepherd of his flock. Using this description from Acts, we can see how he had a special position as the chief apostle and leader of the early Church. Using the “fisher of men” reference assigned to Peter by Jesus (Lk 5:10; Jn 21:11), we also see that it’s Peter who is the preeminent fisherman.

He acts on this first during Pentecost, the inception of the Church with Jewish believers, and with the Gentiles through Cornelius. It is through Peter’s preaching and apostolic mission that the Church is literally built, fulfilling Matthew 16:18.

Peter’s commission conveys the “catholic” mission of the church. This defining mark shows that Jesus’ institution of a unitive body was intended to be global (Mt 28:19) and universal, at all times, in its embrace to reconcile mankind to God. This catholicity was seen in 50AD when the apostles preached with authority and appointed successors, and is seen today with their modern successors, the Catholic bishops.

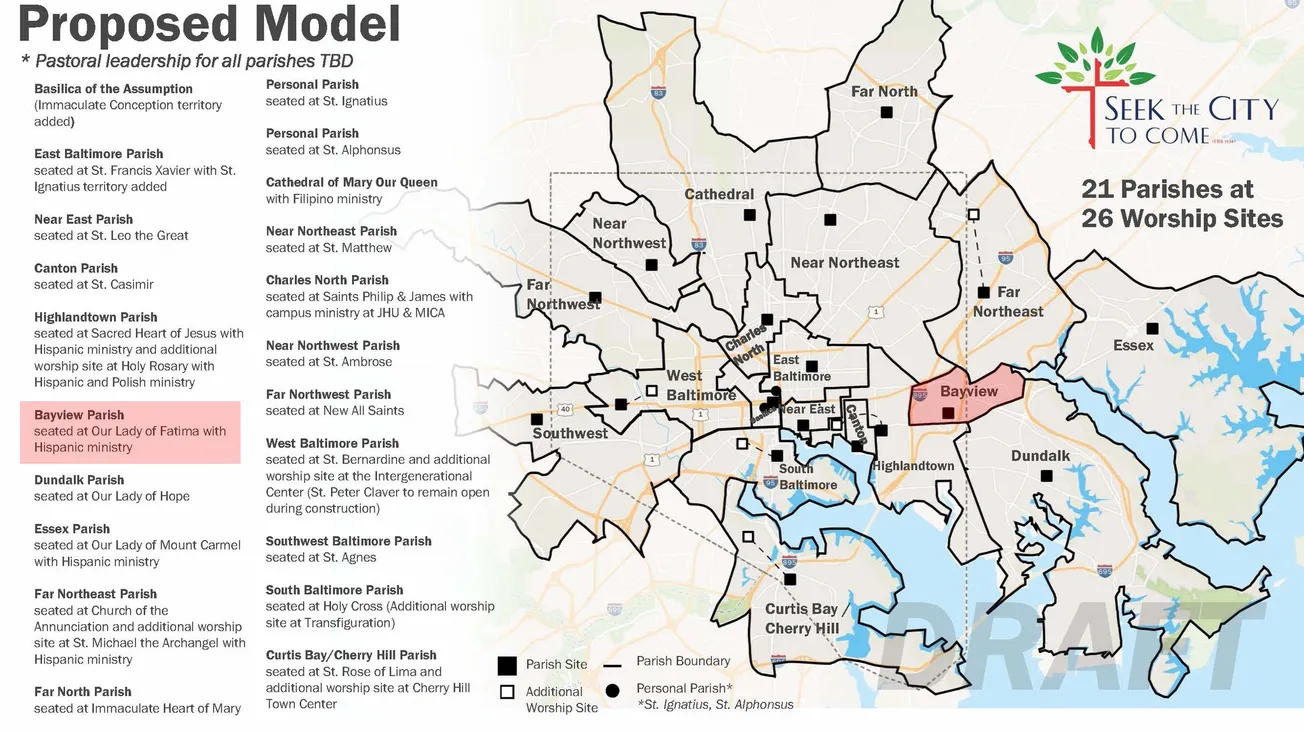

In keeping with Peter’s mission, the Church has work to do in bringing those once displaced into communion with God. Among those within the bosom of the Church, a need for broader representation is evident.

Specifically, for Catholics of African descent, spiritual malnourishment and abuse have persisted for centuries. Examining the failure to consider the Church’s heinous treatment of African-American Catholics, Nate Tinner-Williams stated:

“Considering the disproportionate Black parish closures (some of which were canonically illegal), the continued neglect of Black vocations, the near extinction of Black bishops, and the entrenched anti-Black attitudes displayed by bishops around the country, one can only imagine what would be uncovered if one were to thoroughly investigate the actions of the hierarchy toward African Americans in even just the past century.”

Within the Church, African Americans often feel prolonged neglect, which is contrary to the mark of universality. We possess the Holy Spirit of Christ, generally assent to all the teachings, sacraments, and precepts of the Church, and rejoice in the visible boundaries of the visible earthly Church. So, according to the catechism, we are to be fully incorporated into the society of the Church (CCC 837). We share in being a people called out by God into unity.

In our spiritual home, we are on the margins and in near obscurity, even though Christ has called us by name to the sacred mysteries. In our parishes, Christ is present. In our hymns and spirituals, the Spirit ministers to our needs. Our unique style of ancient worship and song is united and elevated in the one true Church, which we profess is holy and apostolic.

We are its true members, just like those of other ancient rites and ethnoreligious Catholic communities, yet we are far too often despised and chastised by the clergy in our land. We are truly a group that knows the intimacy of the Cross.

As with Cornelius, we African-American Catholics are also members of the divine Kingdom. Daniel Rudd, the famous Black Catholic journalist, once stated:

“The Catholic Church alone can break the color line. Our people should help her to do it.”

And it is through understanding our unique Black Catholic talents, gifts, and strengths that our Church can aid in our well-being.

The Catholic priest says of God during the Eucharistic Prayer at Mass: “By the power and working of the Holy Spirit, you give life to all things and make them holy, and you never cease to gather a people to yourself.”

God never ceases in calling mankind, from all corners of the world, back to himself. He called Abraham, the twelve apostles, seventy disciples, and each of the world’s African-American Catholics to the altar of the Eucharist.

Efran Menny is a husband, father, and small-time writer. He’s a passionate educator, student of social work, and host of the "Saintly Witnesses" podcast.