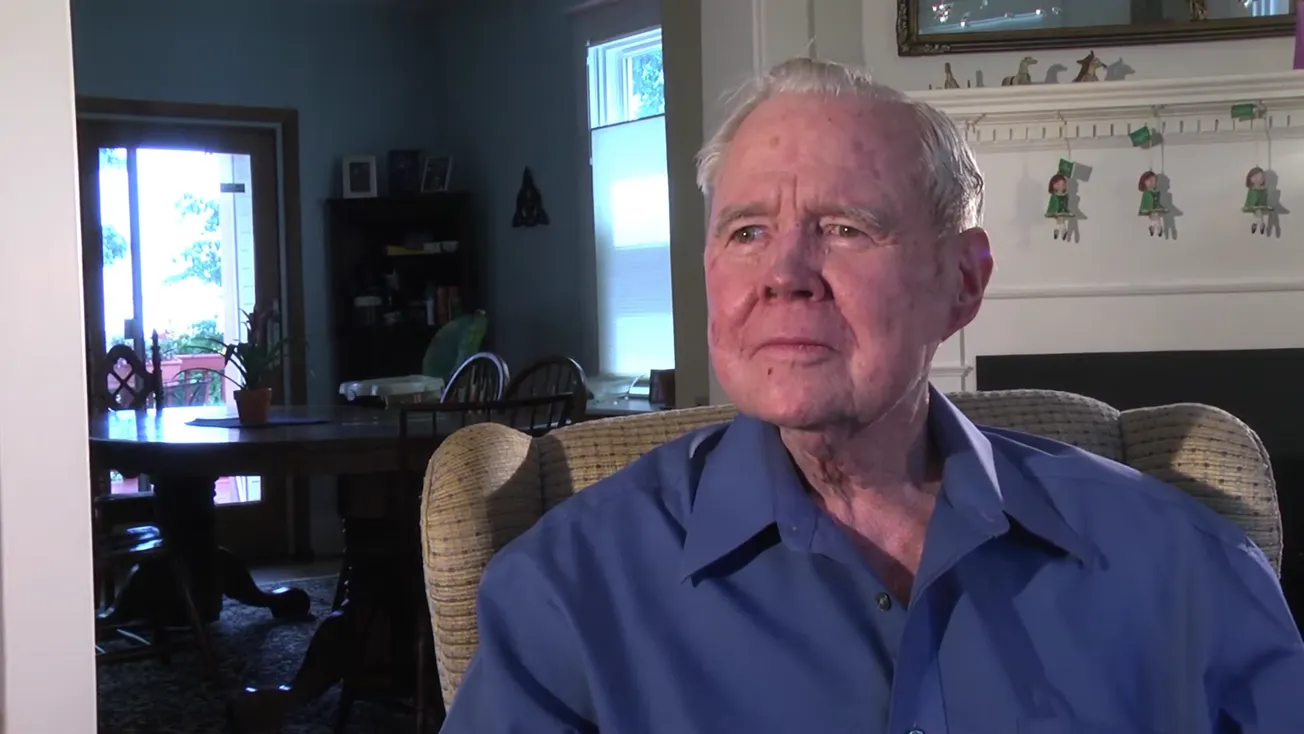

Vincent Patrick Quayle, a former priest who lived in Maryland, helped a whole lot of Black people get decent, affordable homeownership in Baltimore. He died last month.

Vinnie and I met by chance standing in front of St. Frances Academy years—no, decades—ago. He was a Jesuit, dressed in all black as they do. I said hello, not knowing he would one day be my boss at St. Ambrose Housing Aid Center (SAHAC), or that he would assign me to work in Johnston Square, St. Frances’ neighborhood, as a pre-purchase counselor.

The Oblate Sisters of Providence, who sponsor the school, asked Quayle for housing assistance in their neighborhood just as I came to the housing assistance agency. I thought I’d be working in the office on 25th Street, teaching people how to buy a house and advising them on what they could afford. Little did I know that he’d be assigning me to one of the toughest neighborhoods in Baltimore. (The median household income there in 1978 was $4,400 and street crime was rampant.) And little did I know that Johnston Square in East Baltimore would become my all-time favorite place to work. The neighborhood and its people became very dear to me. It was Vinnie whom I had to thank for my wonderful work experience.

Quayle was a native New Yorker, born in 1939 to working parents, Clarence and Kathleen (McGoldrick) Quayle. He went to private school at Brooklyn Jesuit Prep, then at Villanova University for undergraduate studies before entering the Jesuits. He studied at St. Andrews-On-Hudson Novitiate, Loyola Seminary in Shrub Oak, New York, and Woodstock College in Baltimore County. He was ordained a priest in 1970.

Baltimore City was very different back then. There had never been a Black mayor and only a very few African Americans had ever served on the city council. The real estate industry was racially prejudiced in most segments of the business, with agents stealing from both sellers and buyers. White sellers were scared into selling at lower prices than the market value of their homes as they fled the city. (“The Blacks are coming into your neighborhood! Sell fast and run!”). Black families anxious to become homeowners, with too many unaware of the homebuying process, paid inflated prices for their homes. In the middle of transactions between White sellers and Black buyers were manipulative realtors who built their fortunes based on White Supremacy.

Incidentally, in those days, the real estate business was itself racially segregated with White agents and brokers called ‘realtors’ and Black ones labeled ‘realtists.’ There were too few Black agents to meet the burgeoning demand for home ownership in the Black community, so Vinnie created SAHAC to help.

He did the three most stressful things one can do at the relatively same time: he started a new job (director of SAHAC), moved into Charles Village (Abell Avenue), and—after leaving the Jesuits—found and married the love of his life (his beautiful bride, as he affectionately called her, Pat Connolly). They had three sons: Tom, Matt, and Dan, who were the pride of the family.

SAHAC grew over the years, starting with a small staff of counselors on homebuying, then default and delinquency counselors for those falling behind on mortgage payments. Then came legal services, home rehab loan advisers, a home-sharing program, and incubating assistance for others wanting to start an independent housing assistance nonprofit.

Vinnie and his co-founder and primary co-administrator, Fr George Bur, SJ, hired other ex-Jesuits (Joe Delclos and Frank P. Fischer), neighborhood folks (Shirley Rivers and Anna Davis), service corps volunteers each year, several Black alumni from Loyola High School, and lawyers (with too many names of the varied staff members to mention). The staff, which peaked at about 50, were talented, hard-working, innovative, and very caring individuals. The staff was considered one of the best in the nation for its creativity and effectiveness. In some ways, the staff’s quality was a testament to Vinnie’s charisma and his commitment to putting good people to work helping others.

One such staffer, Brendan Walsh—co-founder in 1968 of the Catholic Workers’ Viva House with his lovely wife, Willa Bickham—recently described what SAHAC meant to him:

“First, prior to my working with Vinnie and the St. Ambrose staff, I never seriously considered the importance, even the necessity, of homeownership for the low-income working poor. I quickly learned that homeownership was fundamental for lasting security and stable living. Second, the St. Ambrose staff, Vinnie, Frank Fischer, George Bur, and Ralph Moore, helped me understand how neighborhoods are manipulated for profits and, often, for the exclusion of citizens. I learned how banks operate, what flipping means, and why some neighborhoods flourish and others go down the drain. I always looked upon St. Ambrose Housing Aid Center as a community of folks dedicated to ‘making the odds a bit more even.’”

Harold and Shirley Milledge, an African American couple, bought a house in the Hoes Heights neighborhood situated between Roland Park and Hampden.

“In 1986, my husband Harold and I were looking to buy our first home. We were sent to St. Ambrose by a good friend, and they put us in touch with someone on staff who helped us to look for things the seller should fix. Michael Guye, a pre-purchase counselor, helped us to get the asking price lowered. We have lived happily in this house for 37 years.”

It was Vinnie Quayle’s vision to help Black people have the same opportunity as Whites to acquire a decent, affordable house to call their own. As if in response to the modern ordeal, a Greek asked in Athens centuries ago, “When shall we have justice in this city?”

The answer that came back? “We shall have justice when those who are not injured are just as indignant as those who are.”

Vinnie was indignant enough to create a vehicle for racial change and economic justice, and with it, he helped a whole lot of people. On behalf of the working poor in Baltimore: thank you, Vinnie. Rest in peace.

Ralph E. Moore Jr. is a lifelong Black Catholic, educated by the Oblate Sisters of Providence and the Jesuits. He has served on various committees on race, racism, and poverty for the Archdiocese of Baltimore. He is a married man with two children and four grandchildren. He is currently a weekly columnist for the Afro-American and a member of the St. Ann Social Justice Committee. He can be reached at vpcs@yahoo.com.