February is a special month for many Afro-Caribbean people. Black History Month is one of the few times when there is an explicit fixation on our existence. The blast to the past during these 28 days is paradoxical, however. While on the one hand we can look back with pride and admiration, it also remains a sharp reminder of the pain inflicted on us. It forces us to confront the outcomes of the carefully orchestrated systemic oppression of Black people and the harsh consequences of this reality.

Racist ideologies, which equipped governments with the tools needed for societal structures that dehumanize Black people, have been pervasive. Despite divine instructions to uphold human dignity, religious entities adopted these ideologies as well. Even the Jesuits, an order of Catholic priests with a radical reputation in the religious world for cultural competence, failed to see through these mythological narratives. This is evidenced by a diary entry found in The Jesuit Minister’s Diary of Grand Coteau, written in Louisiana by Albert Biever, SJ in 1875. The document shows that Black men were prevented from joining American Jesuit communities because their dark skin and hair texture were viewed as innate signs of inferiority.

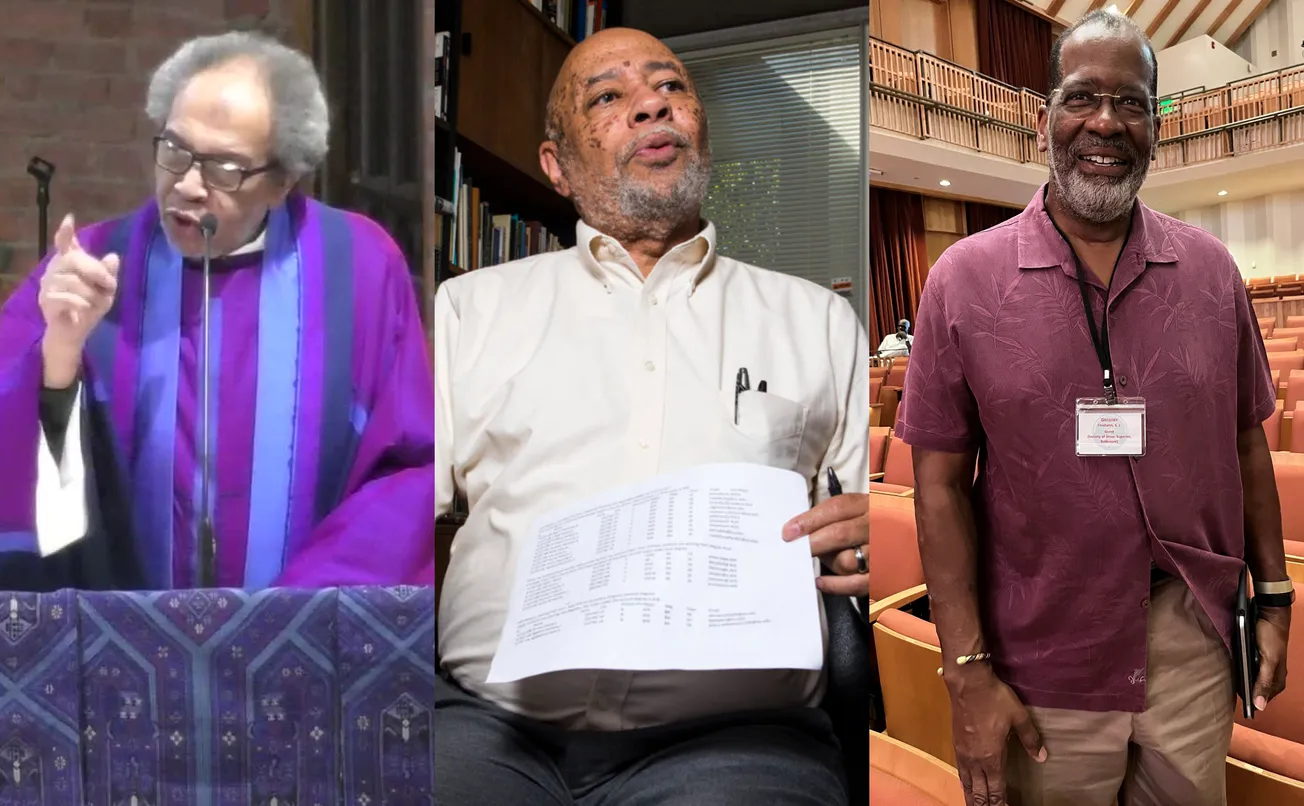

Although some may reduce such a practice to a regretful relic of the past, they’d be making a grave mistake. While Black men are no longer prohibited from joining the order because of their physical features, recent testimonies found in Dr. Lorenzo McDuffie’s 2022 study, “Fully Formed: To Be Black and Jesuit,” reveal that racist practices and attitudes still cause Black men to leave U.S. Jesuit communities today.

A constitutional assessment of statements from the study makes clear that the Jesuits’ treatment of their Black members violated the very principles the order was founded upon in the 16th century.

The Jesuit Constitution is an internal guidebook that governs the operations of the order, which is today the largest in the world. It was initially formulated by St. Ignatius of Loyola, the founder of the Jesuits, in the 1550s. Therein, a chapter entitled “Fostering Union in the Society” provides instructions for how congregations should achieve group harmony. It states that “the need to acquire highly specialized skills for highly specialized works” has a direct relationship with “the preservation of unity of purpose.” It also states that creating this relationship between specialized skills and work is of “prime necessity.” To ensure this constitutional requirement is met, the regional deployment of a Jesuit is to be negotiated by a consideration of their spiritual skillset during communal reflection.

However, McDuffie—a former Jesuit seminarian—reveals in his study that the settings to which Black Jesuits in America were sent to serve were often strictly determined by their skin color. Black Jesuits reported being sent to serve in impoverished Black communities despite not having the tools needed to generate any seismic change therein. For instance, they voiced that they didn’t have the societal comprehension needed to understand these racially traumatized individuals on a deeper level. Merely sharing a racial identity with them wasn’t going to bring success.

Since the unique talents and traits of Black Jesuits had no connection to the “specialized work” they did, their missions did not feel special at all. Imagine leading a life of internal investigation to hone your individual strengths for the sake of helping others, only to have these strengths blatantly ignored due to your race. Any hope of remaining satisfied with your work life would breach the boundaries of reality.

Now, given the order’s public perception, one might want to give these Jesuit superiors the benefit of the doubt. Maybe they had good intentions and just fell into the trap of lazy thinking, leading them to mistakenly conclude that Black Americans’ experiences are monolithic. However, such dreadful decision-making might be motivated by much more concerning thought patterns. One Black Jesuit stated that his congregation assumed Black neighborhoods were dangerous and simply didn’t want to risk the safety of White members. Another felt his superiors didn’t think renewing relationships with Black people was a serious area of concern, so they deferred all reconciliation work to its Black members. Regardless of the reason, when it comes to dealing with Black Jesuits, the relevant section of the order’s constitution obviously wasn’t critically considered.

Another section of the same chapter of the Constitution declares that “communion among all members of the Society” becomes possible when individuals have “an attitude of mind and heart that esteems and welcomes each member as a brother and friend in the lord.” Such attitudes should be marked with “the love and charity which the Holy Spirit writes and engraves on their hearts.” However, responses to Black Jesuits’ complaints of racism show that the Holy Spirit might be seen to be lacking in the hearts of other members.

Instead of having their complaints heard with humility and care, the study shows that Black Jesuits were often villainized and accused of disrupting group harmony. In some instances, their complaints were simply met with silence. In what world can anyone develop meaningful bonds with their colleagues when those confreres are committed to invalidating their emotions? This behavior made any social cohesion impossible.

Themes of assimilation were also quite visible in “Fully Formed: To Be Black and Jesuit,” which makes clear that Black Jesuits weren’t accepted as “brothers in the Lord.” Since God made us in his image and likeness, he wants us to appear as our authentic selves. Back Jesuits, however, felt a strong pressure to conform to White cultural norms, causing an appreciation for their racial identity to slowly disappear. The systemic centralization of Whiteness prevented these Black Jesuits from feeling like they belonged in these settings. Despite the Constitution’s emphasis on promoting brotherly love, these communities failed to foster a fraternal appreciation for their Black members.

The Jesuit Constitution also states that “societies should be strengthened” by “establishing task forces and workshops for reflection.” However, the reluctance to implement any useful community-wide reflectional activities, so that Black Jesuits could feel humanized in such alienating environments, demonstrates that this part of the constitution was ignored as well. The research study shows that when those in leadership roles were urged to address complaints of racism, they did the bare minimum by implementing ineffective training programs. Such a lazy response was seen as a symbolic gesture, failing to bring any substantial change. This only exacerbated the division between non-Black and Black Jesuits.

The congregation’s leaders’ reluctance to designate any reflection spaces solely for Black Jesuits made it more difficult to strengthen connections among each other as well. Due to constantly being ignored, Black Jesuits in America felt they needed a spot where they could together unpack the intense emotions that come with enduring everyday racism. The opportunity to reflect on personal experiences while listening to fellow Black members would allow intimate friendships to form through showing compassion and support. However, apathetic attitudes from those in leadership meant that Black Jesuits had to cope without any institutional support.

If the experiences of Black Jesuits can teach us anything, it is that anti-Black racism hasn’t left these religious and secular institutions. It has only changed in the way in which it manifests. This month, dedicated to our history as African-descended people, must serve as a reminder to those in influential positions of the need to dig deep and rigorously examine how the residue of harmful ideologies continues to strip Black people of their dignity. Until those leaders properly commit to this, Black people will continue to struggle in settings that were never built for them.

Kevin Tachie is a third-year student at the University of Manitoba. He is majoring in Sociology and minoring in Catholic Studies.