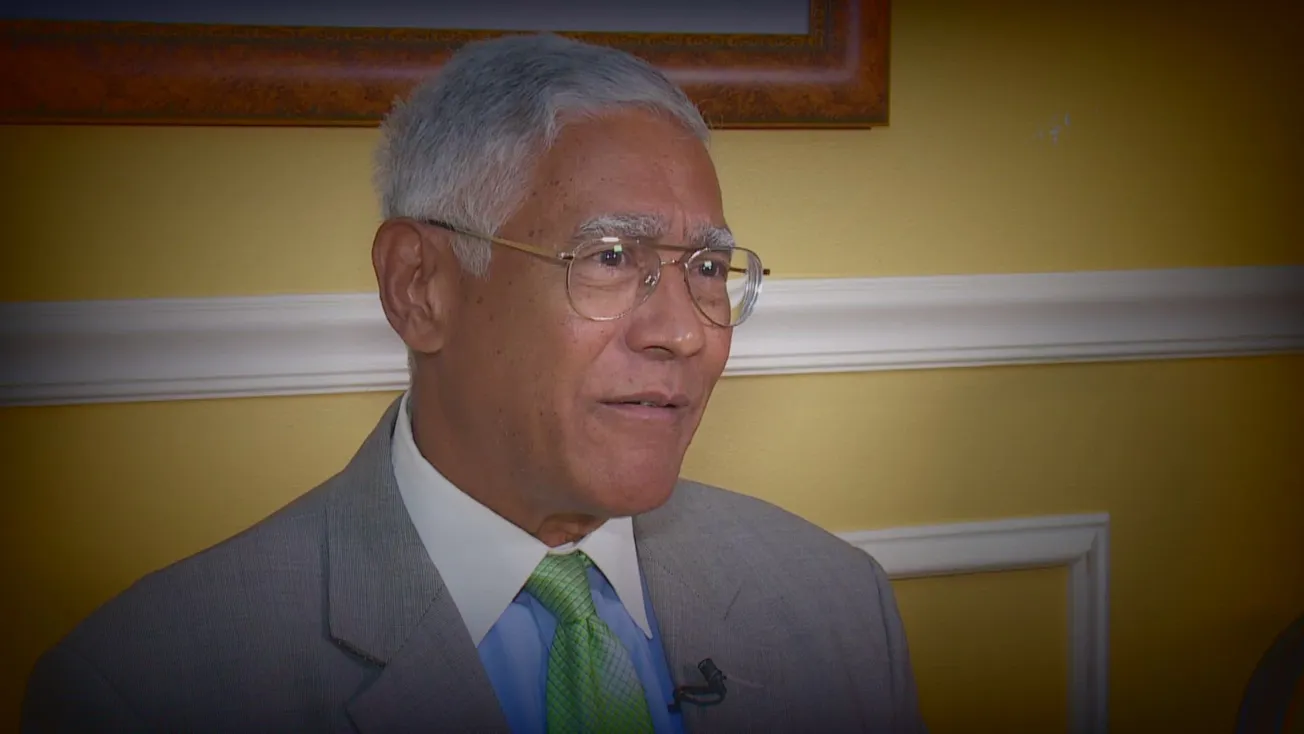

Renault A. “Reggie” Robinson Sr., a nationally known law enforcement officer in Chicago and tireless advocate for minority inclusion on the force, has died after an extended battle with cancer. He was 80 years old.

“He was a pioneer in the fight against racism in the Chicago Police Department and made significant contributions to the city’s housing authority,” his family said in a statement earlier this month, following his death on July 8.

“He will be remembered as a tireless advocate for social justice and a champion of the city’s poor and underserved.”

A lifelong resident of Chicago, Robinson was born in 1942 as the oldest of eight children in a Black Catholic family on the South Side. He attended the former Corpus Christi Catholic Church and School, before choosing a career in law enforcement while in his early 20s.

Robinson was sworn in as an officer in 1964 and within a few years was responding to the rampant racism endemic to the heavily Irish police force in Chicago.

Robinson co-founded the Afro-American Patrolmen’s League (AAPL) in 1968, meant to give Black Chicago officers an outlet to find community, express their concerns, and press for more decision-making power in their profession. They operated under the motto “Black Power through the Law” and were formed as a direct response to Mayor Richard J. Daley’s “shoot to kill” order during local riots in the Black community after the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

“[Robinson] refused to bow down to an unjust system,” said Fr Michael Pfleger, Robinson’s pastor later in life at St. Sabina Catholic Church in the Auburn-Gresham neighborhood.

“He spent his life not just seeking to increase the number of Black officers, but more importantly, he was dedicated to dismantling the system that was keeping out and holding them back.”

The AAPL was also heavily involved in reforming the CPD’s aggressively anti-Black policies in Robinson’s own neighborhood, where infamous police commander Jon Burge ran what has been called “a military-like occupation of Chicago’s South Side.”

Robinson became personally involved in a number of high-profile cases of injustice involving the CPD, opposing the police role in the assassination of Black Panther leader Fred Hampton Sr. in 1969, as well as the ensuing attempt by the CPD to apprehend Hampton’s second-in-command, Bobby L. Rush—who hid in a local Black Catholic parish, Holy Angels Catholic Church.

“When Rush eventually surrendered himself, he did so under escort by [Robinson],” Dr. Matthew Cressler wrote in his 2019 book “Authentically Black and Truly Catholic,” which covered Chicago’s central role in the late 20th-century Black Catholic Movement.

The AAPL, along with Robinson, was a prominent voice in opposing racism in the Chicago Archdiocese, which for decades had refused to promote any of its few African-American priests to the role of pastor. Robinson was among those who pressed the chancery to appoint firebrand activist Fr George Clements—Hampton’s eulogist—as pastor of Holy Angels in 1969, where Robinson then transferred his membership as a show of solidarity.

The next year, Clements and Robinson would team to oppose Chicago’s eminently popular St. Patrick’s Day Parade, which they saw as a symbol of the city’s entrenched White Supremacy. They organized a Black St. Patrick’s Day celebration instead, in which they dyed the South Side’s Washington Park lagoon black. That same year, the AAPL brought a successful civil rights case against the CPD, alleging discrimination against Black, Latino, and women police officers.

“Both Robinson and Clements served as liaisons connecting the Holy Angels community to the broader social and political struggles of Black Chicago,” Cressler wrote.

A member of the CPD until 1983—facing various forms of retaliation from his superiors due to his work with the AAPL—Robinson resigned to join the Chicago Housing Authority under Harold Washington, the city’s first Black mayor. Robinson had previously backed Washington’s 1977 campaign and as CHA chair was a major advocate for public housing projects. His various other actions as chair generated no small amount of controversy, however, and he resigned in 1987.

At the turn of the millennium, Robinson shifted to entrepreneurship, serving as head of his own facilities and maintenance company, making a point to hire from underserved communities in the city. He was also a member of several boards, including the Chicago Urban League and the NAACP. His life and activism was included in various forms of media, including the 1977 book “The Man Who Beat Clout City,” the 1990 docuseries “Eyes on the Prize,” and the 2015 documentary film “The Black Panthers: Vanguard of the Revolution.”

Robinson is survived by his wife Annette, four sons, 10 grandchildren, and six siblings. He was preceded in death by his parents, Robert Sr. and Mable Robinson, and his brother, Robert Jr.

A funeral Mass will be held for Robinson on Tuesday, July 25, at St. Sabina, where a number of Chicago’s major public figures are expected to be in attendance, including the Rev. Jeremiah Wright and Minister Louis Farrakhan.

Nate Tinner-Williams is co-founder and editor of Black Catholic Messenger.